There have been a number of technology innovations in the field of software development over the last five or ten years. Cloud computing, Hadoop, and NoSQL are just a few technologies that have seen reasonably quick growth and adoption. But in terms of long-term effect on the software industry, these technologies are miles behind a relative newcomer.

That technology is docker.

What's Docker?

Docker is an application build and deployment management system. It is based on the idea of homogeneous application containers. The shipping industry has long realized the benefit of such containers.

Before an industry standard container existed, loading and unloading cargo ships was extremely time consuming. All of this was due to the nature of the shipping containers: they were all of different sizes and shapes, so they couldn't be stacked neatly or removed in an orderly fashion. Once a standard size and shape were agreed upon, it revolutionized the industry.

New infrastructure could be built that dealt only with containers of a single size. Loading and unloading became orderly and automated. And shipping things got a lot faster.

OK, But What Is Docker Really?

Docker consists of containers, based on preexisting technologies like lxc and union file systems. Certainly, launching Linux containers from the command line is nothing revolutionary. However, the containers themselves are only half the story.

The other half is images. Images are indexed snapshots of the entire filesystem a container is meant to run. Every time a change to the filesystem is made, a new version of the image is automatically created and assigned a hash ID.

In one stroke, a number of longstanding problems in managing software systems are solved by Docker:

- Repeatability of deployments: every previous production deployment should be re-buildable)

- Management of applications with conflicting dependencies: two applications that rely on different versions of the same package

- Isolation of orthogonal applications: two unrelated applications that happen to run on the same machine should not be able to negatively affect one another

- Distributed management of virtual environments: a GitHub like repository to manage organization and deployment of application versions

- Low overhead: Unlike traditional virtual machine solutions that require a hypervisor, any solution should be based on much lighter-weight Linux containers

Docker solves all of these issues. I kid you not. Let me show you how.

Flask: Dockerized

Let's see how Docker really works with an existing small (but not trivial) Flask application. It's called eavesdropper and I've written about it previously. Instead of using SQLite, though, we're going to use a big boy database and switch to PostgreSQL (through SQLAlchemy, of course).

Let's actually get the database portion out of the way now, since it's mostly

just boilerplate. We need to create a Dockerfile that installs PostgreSQL from

scratch on a new Ubuntu image (the image we'll use as our base). Helpfully,

this exists as one of Docker.com's tutorials.

Follow the instructions in the article, except when it says to run sudo docker run --rm -P --name pg_test eg_postgresql,

what we actually want to run is sudo docker run -d --name db eg_postgresql,

which will start up a container using our image and call it db for short.

Now that we've essentially taken care of all database deployment tasks, we

turn to the eavesdropper application itself. Clone it from GitHub and take a

look at the Dockerfile. All we're really doing is adding our application's code

to the image, using requirements.txt to determine which packages to load, and

running a script that pre-populates the database and starts the app. Run the

following two commands to build and run the container, respectively:

1 | |

And...

1 | |

The only trickery there is some of the flags in the run command: -d

daemonizes the application, -P exposes ports for communication, and --link

creates a communication link between our container and the db container we

started earlier. What this does is essentially put an entry in the /etc/hosts

file with a db entry and a local IP, allowing our container to connect to the

database container, and that's it.

If everything worked properly, you should be able to run $ sudo docker ps and

get something like this:

1 2 3 | |

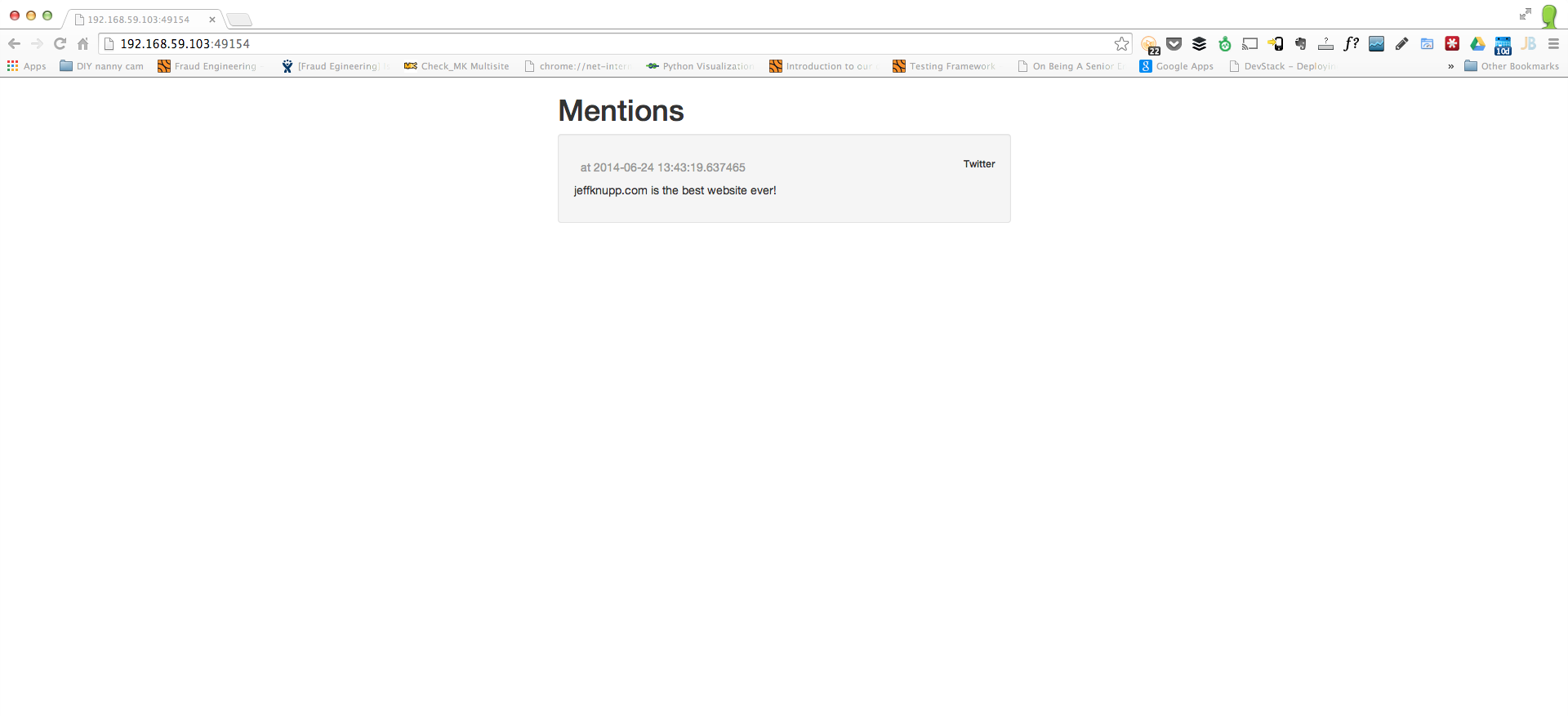

Here we can see that port 8080, which our application runs on, is being mapped

to the local port 49154. You should now be able to open up a browser, point it

to localhost:49154 (or the ip returned from boot2docker ip if you're on a Mac)

and see the following:

A Step Back

Let's take a step back for a moment and assess what we've done. We've created two containers runnable on any host machine capable of running Docker (which is basically any Linux machine). Each is built in a repeatable manner, with the filesystem ensuring no rogue changes make it into the image without us noticing. Most importantly, we've solved our dependency issues before we've deployed our application.

Think about that: the image contains all dependent packages required to run our application. There is no Chef or Puppet step where we provision an entire machine for a single application because of dependency management issues. We just launch containers, and they already have everything they need to run. Two different containers with different versions of the same library? Who cares? We can't see inside the containers; we just run 'em.

It's that black-box aspect of running containers with their dependencies already resolved that makes Docker so compelling. Gone are the days when each machine was given a name that matched the application it ran (and only ran one application). Instead, commodity hardware is finally a software commodity. Machines are just resources used to launch containers. This is big.

A Look Ahead

No technology in recent memory has experienced the rate of adoption that Docker has. It's already supported on all of the major cloud platforms (AWS, Google Compute Engine, Rackspace, etc). This has broad implications for ease of deployment between vendors, as well as dynamic switching or load balancing between heterogeneous cloud providers. As long as you have your image, they'll all run your container in exactly the same way.

If all of this doesn't sound as ground breaking as I make it out to be, it's due to my failures as a writer and is not a reflection of Docker's importance. I've spent the last few weeks thinking about what Docker makes possible and some of these ideas were truly mind-boggling. I urge you to take a few minutes after reading this post and reflect on exactly what this means for the software industry, as everyone from developers to managers to DevOps and SysOps will be affected.

Let the revolution begin.

Posted on by Jeff Knupp